Feeling Congested

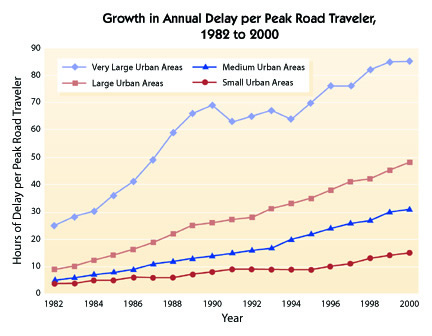

If you're feeling like car travel takes longer than ever, this chart from a U.S. Department of Transportation study on traffic congestion should validate your feelings. Growth of motor vehicles has far outstripped growth of roads, and traffic jams are the inevitable result. Lots of studies have measured the losses in terms of time, money, and pollution. So, aside from getting out of our cars, what are the options for reducing traffic congestion?

Wikipedia presents Anthony Downs' (author of Stuck in Traffic

In a capitalist economy, goods can be allocated either by pricing (ability to pay) or by queueing (first-come first-serve); congestion is an example of the latter. Instead of the traffic engineer's solution of making a "pipe" large enough to accommodate the total demand for peak-hour vehicle travel (a supply-side solution), either by widening roadways or increasing "flow pressure" via automated highway systems, Downs advocates greater use of road pricing to reduce congestion (a demand-side solution, effectively rationing demand), in turn plowing the revenues generated therefrom into public transportation projects. Road pricing itself is controversial, more information is available in the dedicated article. - Wikipedia

Since the cost of building more roads in congested urban areas has become exorbitant (for lack of more space, Los Angeles has even considered double-decker freeways), the usually supply-sided White House agrees with Downs' assessment.

President Bush's fiscal 2008 budget proposal would fund pilot projects that encourage metropolitan areas to experiment with congestion charging as a way to reduce traffic. - Washington Post

One problem with tolling is the economic burden it places on poorer commuters, often the commuters with the longest commutes. However, tolling is the easiest solution today because current queuing technology in the form of metering lights fails to solve the congestion problem.

Why? Well, metering lights look at local traffic to determine how much traffic to allow on a highway. Metering lights fail to consider the accident 10 or 20 miles down the road, or the interchange that has started to back up. They merrily meter cars on to the highway, feeding the growing traffic jam until it engulfs traffic around the on ramp. By then, the damage has been done.

How much traffic fits on a highway?

The California Department of Transportation figures that the maximum capacity of a highway occurs at about 45 miles per hour and about 2,000 cars/hour/lane. - University of Washington

It turns out that automobile traffic networks break down in a way similar to the way Internet traffic breaks down. In both kinds of network, after the traffic surpasses the maximum sustainable flow, it slows way down and it takes some time to recover. The Internet's advantage, of course, is that it's much easier to re-route electrons than atoms. So, the Internet can heal itself by re-routing while the traffic jam lingers until road network demand drops.

To increase lane utilization, one solution is conversant cars that communicate and coordinate with one another. Another solution uses cars with built-in technology to drive themselves. One organization is trying to create a competition like the Ansari X Prize (for private space travel) to stimulate private solutions to traffic congestion. Here's a video that shows how such a system might work:

The problem with solutions built in to cars, though, is the time it takes to introduce such solutions into the market. The costs are prohibitive, too. If tolling seems bad, think about charging everyone $500 or $1,000 for a device that enables conversant or smart cars. Most of these systems require every car to carry the device for the desired traffic decongestion.

This explains why economist Downs proposes tolling to solve the congestion problem. Are we really stuck with tolling to fix the demand side of the traffic congestion problem?

A promising emerging idea is to mix and match tolling and queuing. In this scenario, a driver would check online or call a phone number to make a reservation for a trip. If drivers provide the start and end points of their travel, it is easy to meter traffic correctly because all the traffic patterns can be computed in advance. In the simplest sense, this scenario requires each driver to agree with all the other drivers about the best time to get on the highway and the best speed to drive. It's similar to airline pilots agreeing when to take off so they don't all arrive at, say, JFK airport at the same time. Waiting five minutes on the tarmac is safer, arguably faster, and certainly more fuel efficient than circling with 20 other aircraft waiting to land.

Queuing doesn't preclude tolling, though. In fact, such a system could use tolling to allow drivers to buy earlier reservations. The design of such a tolling system could give paying drivers faster access while delivering the non-paying driver to his or her destination more quickly net of traffic congestion. In other words, the economical traveler would arrive sooner with this system than without this system, even though some drivers are paying for priority reservations. Tolls would pay the cost of deploying such a system. In the long-run, tolls would reduce tax burdens and provide additional funding for road maintenance.

The drawback? Drivers may have to wait to get on a highway. The benefits? Most drivers reach most destinations much more quickly. The costs? Net of tolls, the system can pay for itself.

The queuing/tolling solution has two important side-effects. First, you can fix the supply side problem. By measuring traffic flows through a network, the trip data tell you exactly where to add capacity cost effectively. Since congestion in California probably accounts for something like 1-2% of the state's total CO2 emissions, the second side effect is that this queuing/tolling system reduces greenhouse gases significantly.

My prediction is that you'll see a queuing/tolling system on urban highways in fewer than five years. There isn't any other good solution to congestion.

Labels: competition, congestion, conversant cars, global warming, highways, queuing, tolling, traffic, transportation

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home